Museums accept objects into their collections on a regular basis through a standard procedure called accessioning. While the details of this procedure differ between institutions, at the most basic level accessioning means making an object an official part of the museum’s collection by giving it a unique identification number and adding information about the object into the museum’s database.

But museums change, evolve, and grow. What may have seemed like a good addition to the collection in the beginning of a museum’s existence may become redundant or unnecessary in the future. This is where deaccessioning comes in.

Deaccessioning, as anyone with a knowledge of suffixes might expect, is the exact opposite of accessioning. Where accessioning officially admits an object into the museum’s collection, deaccessioning officially removes it from the collection.

This is not a process that should be taken lightly. Objects should really only be deaccessioned from a museum’s collection for a small handful of reasons:

- The object is beyond the purview of the museum:

In the early years that taxidermy jackalope seemed like a great piece. 10 years down the line though, it might not be within the museum’s scope anymore.

- The object is redundant, there are more duplicates of this type of object in the collection than necessary:

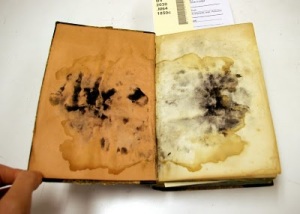

- The object is in such a state of deterioration that it can no longer be kept

This is where I stand right now with one of my projects at the Illinois Holocaust Museum. I’ve been instructed to go through the many books in the museum’s collection (we’re talking a few dozen boxes worth) and make recommendations about what should be done with them. Some are obviously relevant and should be kept: diaries, prayer books that were carried through the ghetto and a concentration camp with a survivor; and some clearly belong in the library rather than the exhibit collections: memorial books about concentration camps, reference books, memoirs of survivors, etc.

Then there are some books that are just no longer relevant to the museum. Prayer books, for instance, are a big one. How many prayer books does one Holocaust museum need? I’m not exactly sure, but I think it’s less than the couple hundred in the collection right now. This is definitely a case of duplicates and redundancy. So if a prayer book was published after WWII? I’m recommending it for deaccession. If I can’t identify anywhere in its documentation how it got from Europe to the US? I’m probably recommending it for deaccession. With hundreds of books currently in the collection, some will have to go. But I’m not the one who has final say on this.

Deaccessioning is not a quick and easy process. Museums need to think carefully before they accept objects into their collection (someone should have thought carefully about that jackalope in the first place…) and even more carefully before deaccessioning.

First of all, I’m just an intern (though an awesome one) so what I say is just a recommendation. No book is going to be removed from the collection simply on my say-so. Instead, my recommendations will have to be approved by the Collections Manager who will need the Director of Collections and Curation to sign off on them as well. Then, like all objects to be deaccessioned at the Holocaust Museum, the removal of the books from our collection will need to be approved by the Board of Directors.

After the deaccession of the books is approved by the Board of Directors, the original donors will be contact to inform them about the decision, why it was made, and to see if they would like their books back. If they don’t, then in the case of prayer books, they will likely be properly disposed of which in the Jewish tradition means a religious burial.